03

de Març

de

2017 - 09:33

Every year between 20 and 30% of the world's harvests are lost due to problems related to noxious fungi or bacteria. These infestations have traditionally been treated with chemical products, with the negative effect that supposes for the plants themselves and the soil in which they are grown. "Chemicals are quicker because they kill everything," points out Maria Isabel Trillas, doctor in Biology and a professor at the UB. She is one of the people behind Biocontrol Technologies, a spin-off from the UB that has a biological solution for the treatment of these diseases in the soil and plants. It is a microorganism, a trichoderma, which along with the product T-34 Biocontrol protects the plant with a vaccine effect and helps it to absorb nutrients so that it grows more, is greener and gives larger fruit.

In practice, farmers get a packet of powder that is dissolved in water and added when watering the crops. "We looked for a product so that farmers would not have to change their system of application," says Trillas. They are now in 20 states in the US, while their product is also sold in Europe in the UK, Ireland, Hungary, France, the Netherlands, Belgium, Spain and Portugal. They are also in Egypt and soon to be in Italy, Morocco, Kenya and Japan.

Walking through the death valley

It could be said that Biocontrol is currently experiencing its best moment. Sales are growing and markets expanding, but to get here has been a long and difficult road. Despite having the patent for the microorganism since 2002 and setting up the spin-off in 2004, sales did not begin until 2011. The reason is that the market is highly regulated and obtaining approval requires patience.

In Europe, it has to be shown that the material serves for each plant in each state. In the US, however, the process is a little quicker because studies from outside the country are accepted.

Once the spiin-off was set up, Trillas recalls that "it took us four years to do all of the tests: some 150 studies." The resulting documentation took years to be approved and accepted at a time when non-chemical proposals were just beginning to appear. Nevertheless, between 2007 and 2010, Biocontrol had a provisional permit to sell in Spain, "something that helped us to survive with the sales we made, but also to get experience about the response from farmers," says Trillas.

Whatever the case, Biocontrol preceded the determination of European institutions to reduce pesticides and create new products. "We were pioneers, with all the advantages and drawbacks that come with it," the biologist points out. Brussels reviewed and harmonised all the products on the market, withdrawing 74% of them. "That meant a lot of distributors were left without products to sell," says Trillas. As a result, large multinational chemical firms like Bayer began to buy up small companies producing biological products, as it did with Agraquest for 450 million dollars.

It was this scenario that allowed Biocontrol to survive until the product was ready to go on the market. "The distributors, on seeing that the large multinationals had begun to do this and without enough regulated products, gave us non-refundable money for the distribution rights," says Isabel Trillas. That is what kept them going during their travail through their own 'death valley'.

"At the start everyone invests money because it is biotechnology," says Trillas about the first private contributions to the product, apart from institutional funding. "The problem comes when the process moves ahead. If it were a pharmaceutical product it would be worth more each time, but here is where you enter death valley. The processes took time, Europe moves slowly and people begin to doubt you will pull it off."

Scientific entrepreneurs

"A researcher normally makes a patent and hands it over. But we took time to see that it would work everywhere," recalls Trillas. With the tests carried out in different places they began to see that "the product stood up to all situations and that the effort was worth it." Being a product with a wide range meant they had more work, but "now it can bring in more sales," she says.

Today, four people work at Biocontrol along with the founder members, who combine their work at the university with growing the company. Trillas, who is a finalist for the EU's Women Innovators prize for 2017, says that they have decided to focus on the part that can contribute most value, the registration and development; farming out the manufacturing and distribution. "But one day I would very much like to have a factory," she says.

With the large multinationals buying up companies with their profile, Trillas insists that "the offers they made to us, as they were not for millions, were not worth it." Whatever the case, she makes it clear that the aim is to be independent so that "we can implement strategies that are different from those of the chemical companies."

In practice, farmers get a packet of powder that is dissolved in water and added when watering the crops. "We looked for a product so that farmers would not have to change their system of application," says Trillas. They are now in 20 states in the US, while their product is also sold in Europe in the UK, Ireland, Hungary, France, the Netherlands, Belgium, Spain and Portugal. They are also in Egypt and soon to be in Italy, Morocco, Kenya and Japan.

Walking through the death valley

It could be said that Biocontrol is currently experiencing its best moment. Sales are growing and markets expanding, but to get here has been a long and difficult road. Despite having the patent for the microorganism since 2002 and setting up the spin-off in 2004, sales did not begin until 2011. The reason is that the market is highly regulated and obtaining approval requires patience.

In Europe, it has to be shown that the material serves for each plant in each state. In the US, however, the process is a little quicker because studies from outside the country are accepted.

Once the spiin-off was set up, Trillas recalls that "it took us four years to do all of the tests: some 150 studies." The resulting documentation took years to be approved and accepted at a time when non-chemical proposals were just beginning to appear. Nevertheless, between 2007 and 2010, Biocontrol had a provisional permit to sell in Spain, "something that helped us to survive with the sales we made, but also to get experience about the response from farmers," says Trillas.

Whatever the case, Biocontrol preceded the determination of European institutions to reduce pesticides and create new products. "We were pioneers, with all the advantages and drawbacks that come with it," the biologist points out. Brussels reviewed and harmonised all the products on the market, withdrawing 74% of them. "That meant a lot of distributors were left without products to sell," says Trillas. As a result, large multinational chemical firms like Bayer began to buy up small companies producing biological products, as it did with Agraquest for 450 million dollars.

It was this scenario that allowed Biocontrol to survive until the product was ready to go on the market. "The distributors, on seeing that the large multinationals had begun to do this and without enough regulated products, gave us non-refundable money for the distribution rights," says Isabel Trillas. That is what kept them going during their travail through their own 'death valley'.

|

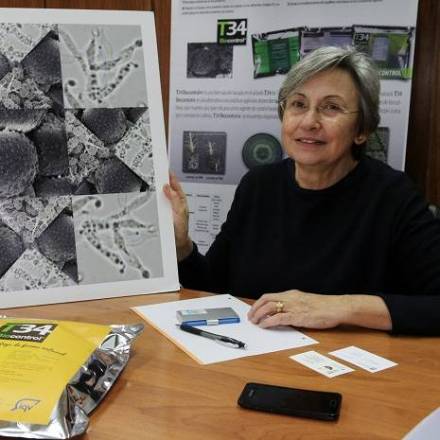

| With this product famers can look after their crops without chemicals. Lali Álvarez |

"At the start everyone invests money because it is biotechnology," says Trillas about the first private contributions to the product, apart from institutional funding. "The problem comes when the process moves ahead. If it were a pharmaceutical product it would be worth more each time, but here is where you enter death valley. The processes took time, Europe moves slowly and people begin to doubt you will pull it off."

Scientific entrepreneurs

"A researcher normally makes a patent and hands it over. But we took time to see that it would work everywhere," recalls Trillas. With the tests carried out in different places they began to see that "the product stood up to all situations and that the effort was worth it." Being a product with a wide range meant they had more work, but "now it can bring in more sales," she says.

Today, four people work at Biocontrol along with the founder members, who combine their work at the university with growing the company. Trillas, who is a finalist for the EU's Women Innovators prize for 2017, says that they have decided to focus on the part that can contribute most value, the registration and development; farming out the manufacturing and distribution. "But one day I would very much like to have a factory," she says.

With the large multinationals buying up companies with their profile, Trillas insists that "the offers they made to us, as they were not for millions, were not worth it." Whatever the case, she makes it clear that the aim is to be independent so that "we can implement strategies that are different from those of the chemical companies."